Since June 2015, I have been reading both parapsychology and philosophy texts relating to the treatment and meaning of “transcendent” experiences in both academia and daily life. I applied theories and perspectives from critical texts, — namely The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature by William James, Spirit Mind, and Brain: A Psychoanalytic Examination by Mortimer Ostow, Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature by M.H. Abrams, and Beyond the Finite: The Sublime in Art and Science edited by Roald Hoffmann and Ian Boyd Whyte, along with numerous essays and articles, — to passages of fiction, poetry, and various case studies, in order to identify how cerebral speculations have continued to be artistically expressed. By analyzing works of literature, I was able to freely interpret and expand upon characteristics of “spiritual” experiences that I had read about.

During the preliminary stages of my research, I sought out reading materials dealing with out-of-body experiences (OBEs), since I was motivated by the widespread resistance of scientific and academic communities to acknowledge the benefits of investigating psi (a term typically used to refer to factors that underlie paranormal experiences and phenomena and extend beyond the quantitative and empirical practices of both natural and social sciences). OBE accounts present explicit evidence of the power of an event over one’s spiritual being because the dual nature of human substance is inherent. Since I had already committed to spending the fall semester in Keene, NY through Hamilton College’s inaugural Academic Program in the Adirondacks prior to obtaining my Digital Humanities CLASS Fellowship, I resolved to seek out writing, art, and personal narratives that demonstrate the strong correlation between the mind/soul/spirit and the magnificent nature of the Adirondack Park. Through the DHi at Hamilton, I would eventually create a database with interactive fiction components to capture the untold stories of a region in the most surreal, and, therefore, the most accurate, way possible in order to inspire public appreciation for the intrinsic imaginative and enjoyable qualities of real stories that are not necessarily realistic according to today’s general standards.

Although my initial goals have not changed much over the course of the summer, I have exposed myself to even more directions my project could go and the implications such could have on communities, individuals, and my own personal growth. Early on, I realized the difficulty of finding resources pertaining to my research interest. However, after obtaining a partnership with the Adirondack Center for Writing that will commence during my fall semester and reaching out to faculty and staff directly involved with the mountain region, I am confident that my decision to focus my study in the Adirondacks will have a significantly positive influence on in the Adirondack and Hamilton community. After speaking with Digital Initiatives Librarian Reid Larson about the opportunities and challenges of his Adirondack Guide project, I am no longer frustrated by the lack of readily available resources, — save literature and art of the Romantic Era, — dealing with personal experiences in the Adirondacks; The utilitarian priority that governs what Adirondack resources are most accessible makes me all the more determined to follow through with my project because of the prospect of increasing tolerance for transcendental pursuits and appreciation for the diverse people that share an intimate relationship with a region that attracts millions of tourists from all over the world.

If I had not delved so deeply into disciplines outside of my Creative Writing major, I would not have been enlightened to the ways parapsychological research and spiritual writings have existed throughout history disguised under a multitude of different terms. In the twenty-first century, terms such as ‘spirituality’, ‘spiritualism’, ‘supernaturalism’, the ‘sublime’, ‘religion’, and ‘mysticism’ are used interchangeably in everyday conversation to describe phenomena that do not comply with common reason and fact. By examining the deeper meaning of words that seemed to be synonymous on the surface, I learned more about what kinds of narratives were important to my project than I ever would have if I had narrowed my search down to terms I was intuitively attached to. The event of an individual feeling the warm presence of a higher being while looking at a pristine vast landscape from the apex of a mountaintop could be described as:

1) a spiritual experience in that the individual is overcome by “an elevating, transcendent, inspiring influence, comforting or fearsome, but attributed to a divine or cosmic source”[1] (29)

2) an encounter with a spirit (as in the spirit of ‘spiritualism’ as opposed to ‘spirituality’) if the individual perceives the as an entity that defies the confines of physicality

3) a supernatural occurrence if the individual claims that what took place had no basis in sensible reality

4) a sublime experience in that the environmental stimulus evokes overwhelming feelings of awe in the individual

5) a religious revelation in the sense that it was an “experience of [an] individual in [his or her] solitude, so far as [he or she] apprehend[ed] [his or herself] to stand in relation to whatever [he or she] considered divine”[2]

and/or 6) a mystical state of consciousness (a term coined by William James in his 1902 collection of lectures The Varieties of Religious Experience used to describe a personal condition that usually coincides with four defining criteria and is the basis of religious experiences) if its qualities can not be properly expressed to others (ineffability), the individual carries with him or her a “curious sense of authority for after-time”[3] (noetic quality), the experience was short and fleeting (transiency), and the individual felt a lack of free will and submissive to the superior power (passivity).

All of the aforementioned terms could lead me to discover vital sources, so at this stage in my project, I am incorporating all of them into my research and community outreach process. Since there is not one word to describe what kinds of narratives I am particularly valuing, I have been inconsistent with regards to what words I use to communicate about and title my project. I do not think the words to talk about what I am spending my summer doing is important now because the task at hand is to gather as much information and primary accounts as I can. It is interesting to note that not only is the practice of trying to represent certain types subject matter inevitably constrained by means of human expression, but so is the way scholars have attempted to label and categorize these subject matter futile due to the ambiguity of language.

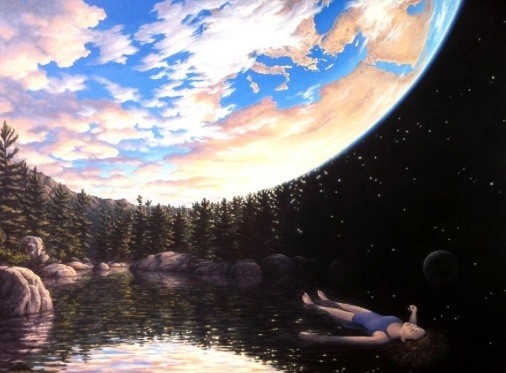

Despite my summer research emphasis on analyzing and categorizing already existing works of literature, the aspect of my project that is the most important to me is the freedom to create my own stories and chronicle my own spiritual development that I purposely arranged for. One of the next steps of my project is to start writing my own fictional story of a quintessential spiritual/out-of-body/mystical/sublime/etc. experience revolving around my experience in the Adirondacks and adapting it to come “alive” on a digital platform to serve as an engaging introduction to the culminating website. I get a considerable amount of my creative inspiration from my vivid dreams, and being rigid with dream journaling has helped me get used to recalling bizarre events and visions and the undertaking of trying to describe in words what only one person, I, can ever truly know the essence of. Our minds struggle to make sense of reality while we are sleeping and make sense of our dreams when we are awake; Poets and artists alike are drawn to the blurred line between sleeping and waking consciousness, between fantasy and reality, between what we can see and what we believe or imagine to be there right before our eyes yet beyond our perception. Romantic poets of England and the frontier regions of the United States were not as distracted and consumed by technology as we are today, and as great thinkers lingered outside in the wilderness, the wilderness gave them gifts of incomprehensible feelings. One of the most vivacious writers I have gotten to know this summer is Wordsworth, and this passage from the first book of Preludes is a graceful portrait of a young boy’s struggle to describe an ominous god-like figure he encountered one evening while sneaking out with a row boat on a lake:

[. . .] but after I had seen

That spectacle, for many days, my brain

Worked with a dim and undetermined sense

Of unknown modes of being; o’er my thoughts

There hung a darkness, call it solitude

Or blank desertion. No familiar shapes

Remained, no pleasant images of trees,

Of sea or sky, no colours of green fields;

But huge and mighty forms, that do not live

Like living men, moved slowly through the mind

By day, and were a trouble to my dreams.[4]

I have also been routinely trying different forms of meditation to enhance my spiritual nature and performing exercises that people who have repeatedly induced out-of-body and psychic experiences recommend to get in tune with my astral self. The personal component of my project has lead me to conclude that my main aim is not to present a historical and societal overview of a region by analyzing the idiosyncrasies of location-specific stories, but rather to illustrate and celebrate how certain personal experiences attribute a timeless, otherworldly quality to a region. Although I have experienced nothing drastically out of the ordinary as of yet, — during this summer or any time of my life, — I am gaining a better understanding of why our own minds are especially fascinating, yet daunting and frightening, in a time and place that constantly distracts us from the unparalleled realms that exist inside all of us.

[1] Mortimer Ostow, Spirit, Mind, & Brain: A Psychoanalytic Examination of Spirituality and Religion (New York: Columbia UP, 2007), 29.

[2] William James, Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (Rockville: Arc Manor, 2008), 31.

[3] William James, Varieties of Religious Experience, 278.

[4] Wordsworth, William, “The Prelude, Book 1: Introduction — Childhood and School-time,” Complete Poetical Works (1888). Bartleby, 1999. Web. 22 Aug. 2015. <http://www.bartleby.com/145/ww287.html>.

Hi Alexa,

Extremely engaging blog post about your project! Let’s discuss options for “One of the next steps of my project is to start writing my own fictional story of a quintessential spiritual/out-of-body/mystical/sublime/etc. experience revolving around my experience in the Adirondacks and adapting it to come “alive” on a digital platform to serve as an engaging introduction to the culminating website.”

Janet

Very interesting Project! Let’s discuss options for the database?

I was very pleased to find this web-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

Dobry przykład oby tak dalej.